Economic instability, a tight housing market, and disinvestment from social welfare programs set the stage for a nationwide homelessness crisis in the early 1980s. Long before then, however, housing had been more available to some Americans than to others. Racism in the South led many African Americans to look for new homes during the Great Migration (1916–1970). Termination and relocation policies (1953–1969) did the same for Native Americans. Redlining and racial housing covenants made it challenging for these and other groups to secure housing.

These factors were in play in Minneapolis in the mid-twentieth century. City planners and business leaders embraced urban renewal and interstate highway construction, both of which removed thousands of units of low-cost housing without replacing them. A 1976 city task force on rental housing reported that rental housing in Minneapolis was “in a state of crisis” that “could not continue in its present form.” By 1978, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimated that more than 57,000 Minneapolis–St. Paul renting households needed financial assistance to afford their housing.

Before 1981, a patchwork of “emergency housing” ensured that most people had a place to stay, at least temporarily. Hennepin County social workers paid for people to stay at residential hotels or the YMCA downtown. City relief workers had a list of private homeowners who would take in mothers with children. Single men could stay at one of two Christian missions. The Urban League, the Native American community, and Sabathani Community Center each had a few units of emergency housing. And domestic violence shelters and youth shelters were developing. In the summer of 1981, however, the waves of housing loss became a tsunami. Minnesota redefined eligibility for General Assistance (GA), a critical financial benefit for people who don’t qualify for other support. The state dropped 58 percent of enrollees, more than 9,000 Minnesotans, from the program between June and November.

People who’d relied on the assistance for their low-cost housing were evicted. The manager of a social service center said the result was hundreds of people looking for help and housing. Native American leaders called an emergency community meeting about the spike in homelessness in the Phillips Neighborhood, and a pastor from Our Saviour’s Lutheran Church brought that call for help back to his church. A member of Holy Rosary Catholic Church told her church that she’d seen evidence of people sleeping in her unlocked car overnight, so she filled it with blankets. A housing activist attending a retreat with St. Stephen’s Church challenged attendees to open the empty, heated part of their building and get people indoors. Hennepin County Social Services kept its lobby open overnight so that people could sleep on the floor or in plastic chairs.

Minneapolis Mayor Don Fraser petitioned the City Council to fast‐track a resolution permitting churches and organizations to shelter people overnight. The council passed the resolution unanimously—but it also added stipulations that limited hours, reduced operation to cold-weather months, and allowed the effort as a “one‐season experiment.”

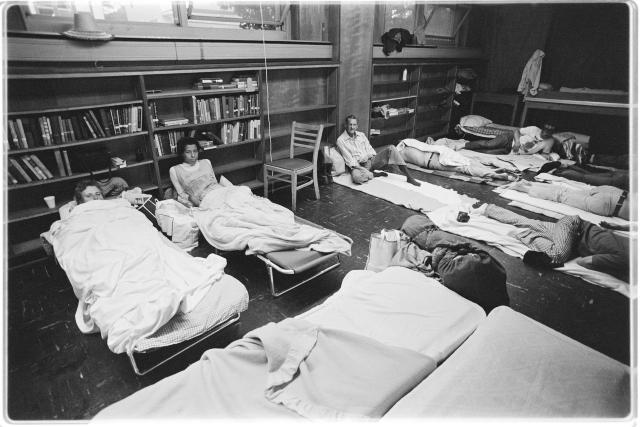

In December 1981, the Minneapolis American Indian Center, St. Stephen’s Catholic Church, Our Saviour’s Lutheran Church, Faith Mission, and Holy Rosary Catholic Church began taking people into whatever spaces they had: a gymnasium, a parish library, a classroom. Catholic Charities worked to streamline referrals to the two missions.

During the following month, January 1982, and throughout that year, another five churches and organizations opened spaces for shelter. The United Way, Hennepin County, and local foundations provided funding to operate the spaces. A survey of shelter guests that year showed that 60 percent had lost some form of government assistance that had been helping them make ends meet—general assistance, social security, or food stamps.

These early shelters were started to address an emergency. Over time, however, they became part of an emerging national housing rights movement that included the Minnesota Coalition for the Homeless, formed through a merger of Minneapolis and St. Paul groups in 1983.

For more information on this topic, check out the original entry on MNopedia.